There exists a wide gender gap in India when various aspects of health are taken into account.

Forget What Women Want, They Don’t Yet Have Access To What They Need: Gender Gap in Health Shows Larger Reality

Even after 76 years of India’s Independence, women lag behind on various counts, and that includes access to healthcare or even using insurance

Even after 76 years of India’s Independence, women lag behind on various counts, and that includes access to healthcare or even using insurance. Given our patriarchal society which tends to subdue women, they study less, earn less, fall ill more and suffer more. Biases, lack of awareness, general negligence and lack of access all play a role in inhibiting women’s access to healthcare.

“We aren’t so concerned about girls’ health as much as we are about boys’. We value boys more,” said Ranjana Kumari, social activist and director of the Centre for Social Research in Delhi.

“Less food or less nutritious food during childhood, as well as thinking about marrying them off soon after, contribute to neglect for girls. From menstruation to pregnancy, we aren’t taking care of girls’ health. This is especially prevalent in villages,” Kumari added.

The disparity has far-reaching consequences. "Absence of timely and adequate healthcare for women and young girls leads to heightened maternal risks, limited economic prospects, educational setbacks, and perpetuates cycles of poverty," said Neera Nundy, Co- Founder, Dasra. "It curtails reproductive rights, exacerbates gender-based violence impacts, and affects mental well-being. These disparities not only undermine women's individual lives but also hinder societal progress, underscoring the urgent need to bridge this gap."

Through the data in this story, we aim to delve deeper into how wide the disparity is, and the challenges that play a role. From broad areas to certain niche ones, we looked at studies and research that’s been done in various parts of the country.

The Gap in Basic Access to Treatment

The basic premise of better health rests on getting adequate care when any illness occurs. That is possible when women are brought in for treatment to leading hospitals. However, data shows how the gender gap is wide on this count itself: patients coming in for treatment.

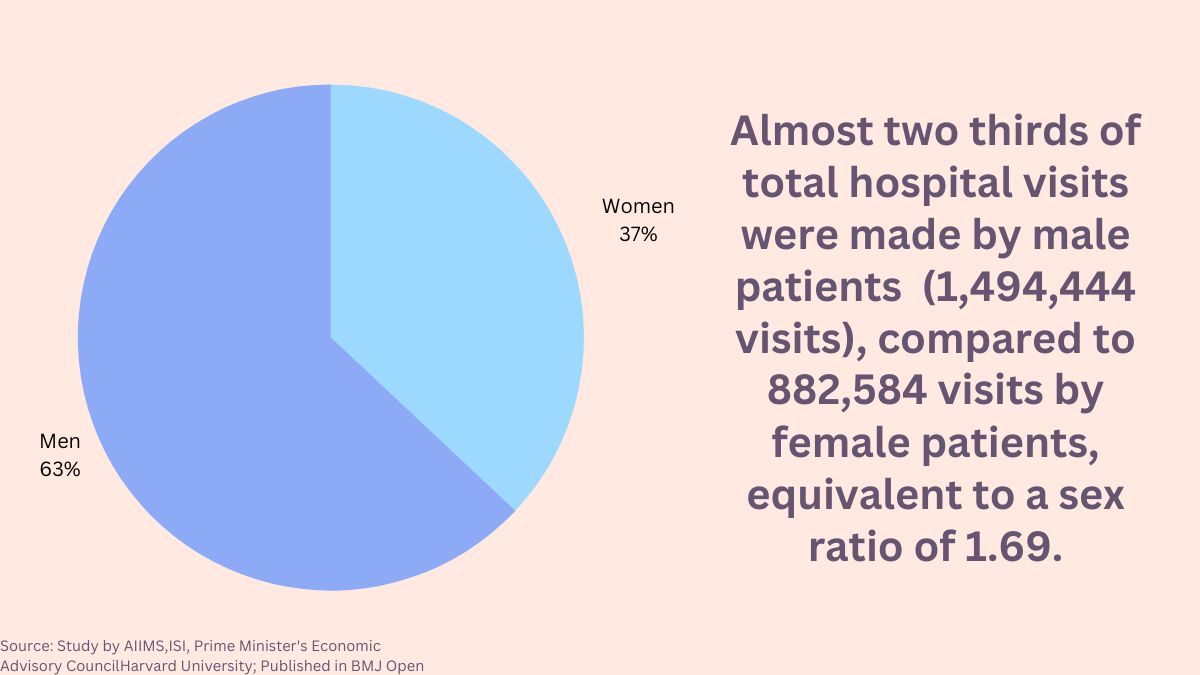

In a study conducted by researchers at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), the Indian Statistical Institute, Prime Minister's Economic Advisory Council, and Harvard University, findings showed a huge disparity between men and women, when it came to healthcare. The study analysed the data of 23.7 lakh people who came to AIIMS OPDs between January and December 2016. The findings revealed that women were only 37% of these patients, while the rest (63%) were men.

The sex ratio stood at 1.69, which means for every one woman treated at AIIMS OPD, there were 1.69 men treated.

Distance from Hospitals Widens Gap

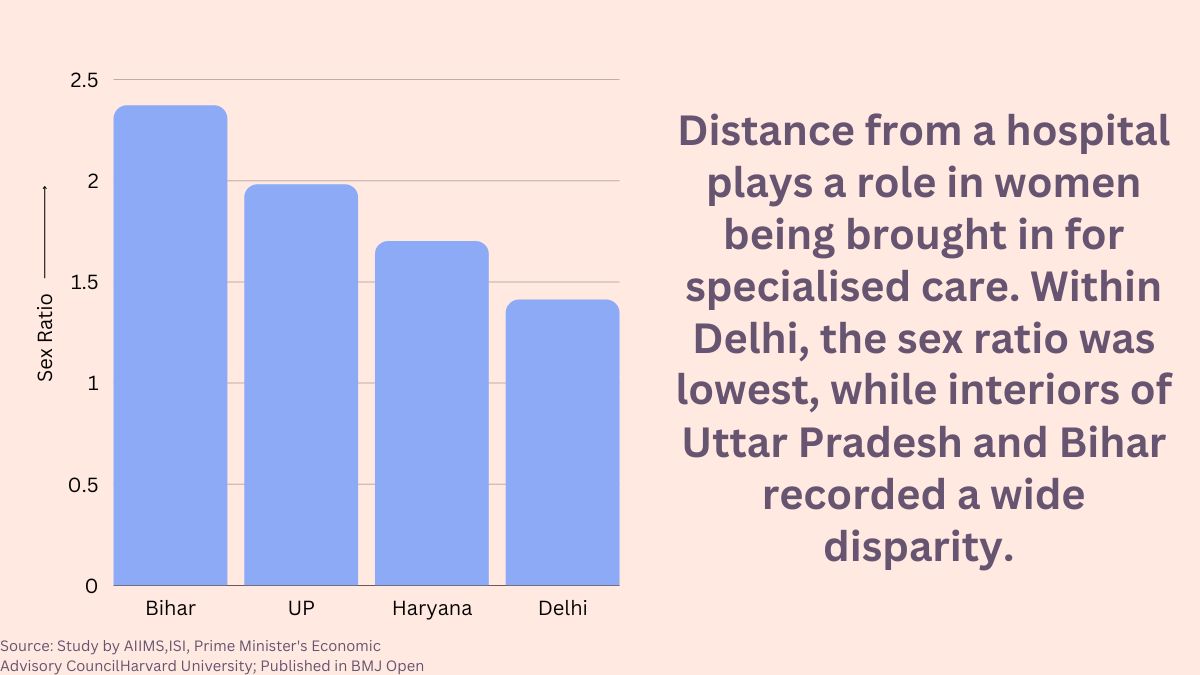

The study showed that the distance from a hospital played a big role in determining whether women were brought in to seek healthcare. In 2016, AIIMS received visits from 84,926 women from Bihar, contrasting with over 2 lakh men from the same state. A similar statistic was true for the interiors of Uttar Pradesh too.

In comparison, the gender imbalance was less noticeable in New Delhi, with female patients totalling 4.8 lakh compared to 6.6 lakh males.

Travel costs appear to be one obvious reason that kept women away from adequate healthcare, though the ticket price is the same for men too.

Youngest and Oldest Suffer Most

Another key finding of the AIIMS study was that the disparity was considerably higher for younger and older age groups, while it was reduced for the middle age groups. This essentially points to how the youngest and the oldest women were the ones most likely to be left out when it comes to accessing specialised healthcare.

India also had one of the highest rates of infant mortality in the world, and, until a few years ago, the female mortality rate was significantly higher than males. However, a 2018 report highlighted that while a gap still exists, it had narrowed down, and was just 2.5% higher than males (39 deaths per 1,000 live births for males and 40 for females). To compare, in 2012 this gap was 10% (54 deaths per 1,000 live births for males and 59 for females).

Women Left Out of Vaccinations

There’s gender disparity even in access to preventive care, such as vaccines that would reduce the chances of illness.

The 2003 National Family Health Survey (NFSH) of India said vaccination rates for female children were 13% lower than those for male children. This difference was particularly noticeable in bigger households and the ones with a higher number of male children. However, the 2015 NFHS data revealed a significant improvement, with the gap having reduced to just 1%.

This divide was also evident in Covid vaccination.

International news outlet DW, in a report last year, analysed the 1.63 billion or 163 crore vaccine doses that were administered in India according to data till then on CoWIN, India's official vaccination website. Of those, 83 crore million were given to men, compared to 79.2 crore to women — which makes for a difference of over 3.8 crore doses.

A digital divide in access to CoWIN, women not being prioritised in rural areas, illiteracy and fear around the vaccines played a part in the gender gap in vaccinations against coronavirus.

Period Poverty

Beyond just the gender gap, there are hurdles for girls and women even in access to menstruation-related healthcare. Widespread period poverty and stigma around menstruation lead to monumental effects, especially on young girls’ lives.

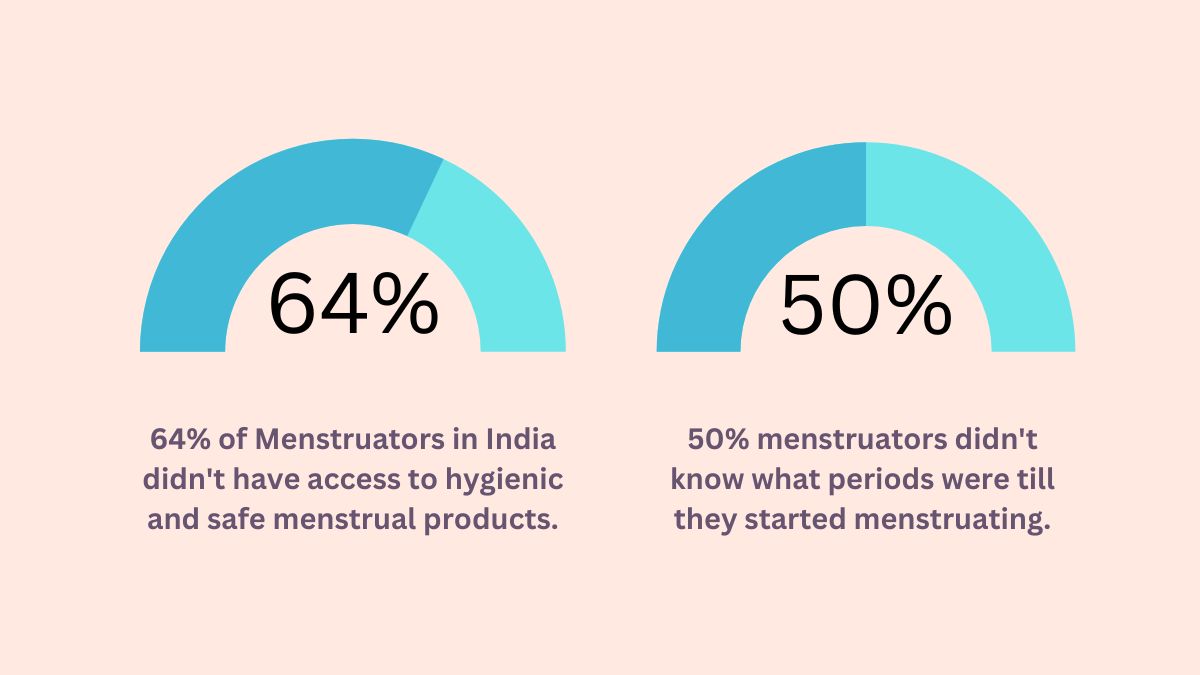

According to the National Health Survey 2015-16, out of India’s 33.6 crore menstruators, only 36% had access to sanitary napkins or safe, hygienic period products. The rest continue to use rags, wool, cloth or hay.

Another study by experts from top institutes – the UK’s Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine; Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai; UNICEF India, and the Centers for Disease Control of the US – found that in a sample size of 1 lakh girls, almost half didn’t know what periods even were, until they started menstruating.

And when girls start menstruating, there is a lack of facilities or aid.

Lack of proper toilets or other facilities, coupled with pain, led to about 2.3 crore girls dropping out of school, according to a report called Spot On by NGO Dasra. Those who don’t drop out, usually miss up to five days of school every month.

These factors form a cycle of neglect for girls, hampering their growth on all levels.

Congenital Heart Disease

Moving away from broad health categories, we delved into nuances, like heart surgery.

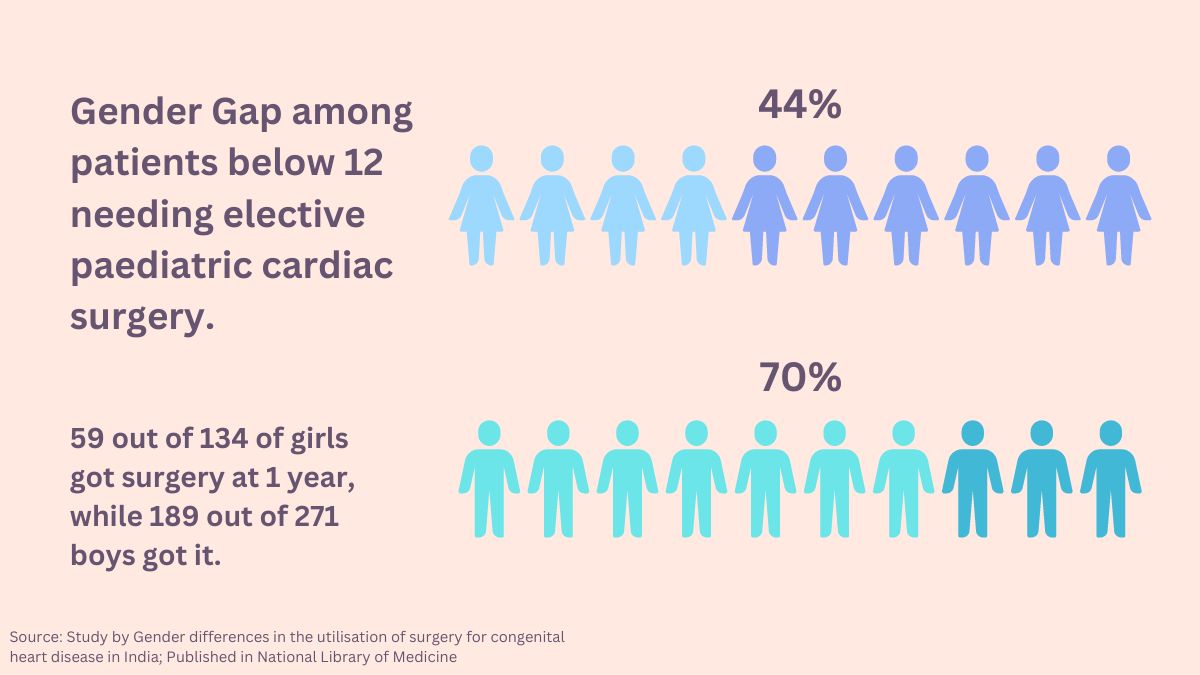

In a study for India published in the US National Library of Medicine, the researchers interviewed parents or guardians of 405 children aged up to 12 years who had been advised to undergo elective paediatric cardiac surgery. This included 134 girls and 271 boys. Among the girls, only 44% had undergone surgery within a year of the doctor’s advice, compared with 70% of the boys.

The researchers then tried to evaluate why parents were reluctant to get the advised surgery for the girls. They found that apprehensions of future matrimonial prospects of girls and lack of social support were major factors. The high cost of surgery too played a role as parents were less inclined to spend on girls.

Maternity Mortality and Care During Pregnancy

Severe bleeding, infections, high blood pressure and unsafe abortions are leading reasons of maternal mortality.

The annual number of maternal deaths in India dropped from 33,800 in 2016 to 26,437 in 2018, according to this report by UNICEF. However, the report also highlights the urban-rural divide, and says that access to health services often depends on a families’ or mother’s economic status and where they reside.

This is corroborated by the findings of another study by experts from Mumbai and Toronto, which analysed “trends in maternal mortality in India over two decades in nationally representative surveys”.

This study found that poorer states had a higher MMR (maternal mortality rate, calculated as death per 1 lakh women who give birth), with the risks being highest in rural and tribal areas of north‐eastern and northern states.

The MMR target set by the UN is 70 per a lakh live births by the year 2030. As of 2020, it stood at 99 for India. But it was actually much worse, at 398 per lakh in 1997, so there has been a big improvement.

The study concluded that “India could achieve the UN 2030 MMR goals if the average rate of reduction is maintained. However, without further intervention, the poorer states will not.”

Sanghamitra Singh, Chief of Programmes, Population Foundation of India highlights that especially in rural India, women don’t have the agency to take their own fertility or health decisions. “Not being able to take these decisions for themselves impacts women across their lifespan. It could be in the form of unwanted pregnancies, early pregnancies, or inability to space out children,” she said. “A lot of this stems from a lack of education and girls getting married at an early age, when they aren’t empowered enough to understand the consequences of unwanted or untimely pregnancies.”

Pregnancy-related complications rank as the leading cause of death among young girls aged 15 to 19. Young girls who are themselves growing, and child brides without awareness of pregnancies, are prime victims of this MMR.

Read: We Asked AI to Depict Indian Scenes. It Generated Sexist, Classist, Biased Images.

Disparity in Usage of Insurance

Even when there is insurance to cover costs, women do not get easy access to healthcare.

A study by researchers at Stanford University analysed over 40 lakh hospital visits under a government health insurance program that entitles 4.6 crore poor individuals to free hospital care in Rajasthan. Females account for only 33% of insurance claims among children and 43% among the elderly.

They found that enrollment for insurance here wasn’t the problem as women were registered for the scheme. But families were more likely to allocate resources to male than female health, leading to poorer utilisation.

Poor Health Hampers Overall Growth and Lives of Women

“In India, women’s health is not a priority, for women themselves or for families. Health-seeking behaviour among women is very low,” said Sanghamitra Singh, Chief of Programmes, Population Foundation of India.

What the numbers and experts point to, is the prevalent prioritisation of men even when it comes to health.

Singh adds that the neglect for women's health is reflected in the nutrition status of women and the unmet need for family planning or contraceptives. “Women want to access healthcare but aren’t able to due to various barriers. Either they aren’t allowed to go out of their homes alone, or they don’t know how to approach a healthcare provider.”

Infrastructure too, plays a big role. Highlighting this, Neera Nundy, Co- Founder, Dasra, said, "Infrastructure for young women, such as the setup of Adolescent-Friendly Health Clinics, when available, is inaccessible and under-resourced. In Jharkhand, and nationally, resource allocation trends for Adolescent Health programs are discouraging, constituting only 2% of the state’s health budget."

Differential status of women, she adds, is all a culmination of social determinants of health, like patriarchy or social norms that ensure that the dice is rolled against women. “If we truly want to empower women, we should invest in changing behaviours or mindsets, of not only the women. We need to address the regressive societal norms. We need to talk to men, families, religious leaders at community levels, and even frontline workers,” said Singh.

The glaring gaps in health, not only affect women but the nation at large. “We need to prioritise women’s health to make progress as a nation. When they go on with life with fragile health, we don’t progress as a society,” said social activist Ranjana Kumari.